Fun and Games in Emacs

It’s yet another Monday and you’re hard at work on those TPS reports for your boss, Lumbergh. Why not play Emacs’s Zork-like text adventure game to take your mind off the tedium of work?

But seriously, yes, there are both games and quirky playthings in Emacs. Some you have probably heard of or played before. The only thing they have in common is that most of them were added a long time ago: some are rather odd inclusions (as you’ll see below) and others were clearly written by bored employees or graduate students. What they all have in common is a whimsy and a casualness that I rarely see in Emacs today. Emacs is Serious Business now in a way that it probably wasn’t back in the 1980s when some of these games were written.

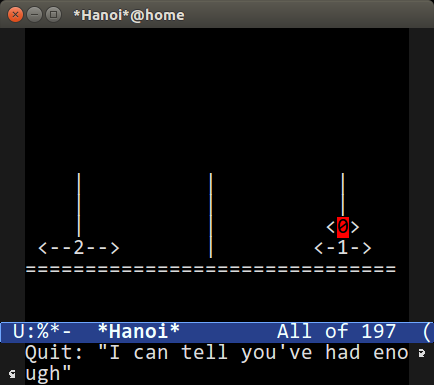

Tower of Hanoi

The Tower of Hanoi is an ancient mathematical puzzle game and one that is probably familiar to some of us as it is often used in Computer Science as a teaching aid because of its recursive and iterative solutions.

In Emacs there are three commands you can run to trigger the Tower of Hanoi puzzle: M-x hanoi with a default of 3 discs; M-x hanoi-unix and M-x hanoi-unix-64 uses the unix timestamp, making a move each second in line with the clock, and with the latter pretending it uses a 64-bit clock.

The Tower of Hanoi implementation in Emacs dates from the mid 1980s — an awful long time ago indeed. There are a few Customize options (M-x customize-group RET hanoi RET) such as enabling colorized discs. And when you exit the Hanoi buffer or type a character you are treated to a sarcastic goodbye message (see above.)

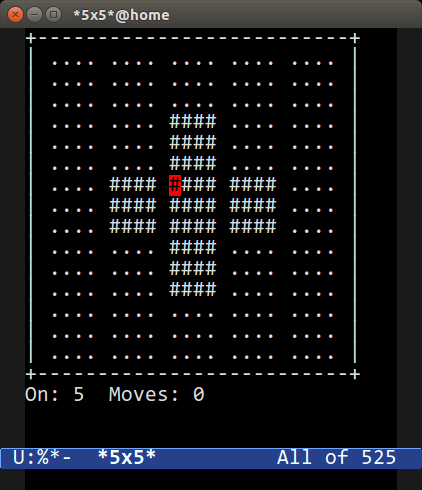

5x5

The 5x5 game is a logic puzzle: you are given a 5x5 grid with a central cross already filled-in; your goal is to fill all the cells by toggling them on and off in the right order to win. It’s not as easy as it sounds!

The 5x5 game is a logic puzzle: you are given a 5x5 grid with a central cross already filled-in; your goal is to fill all the cells by toggling them on and off in the right order to win. It’s not as easy as it sounds!

To play, type M-x 5x5, and with an optional digit argument you can change the size of the grid. What makes this game interesting is its rather complex ability to suggest the next move and attempt to solve the game grid. It uses Emacs’s very own, and very cool, symbolic RPN calculator M-x calc (and in Fun with Emacs Calc I use it to solve a simple problem.)

So what I like about this game is that it comes with a very complex solver – really, you should read the source code with M-x find-library RET 5x5 – and a “cracker” that attempts to brute force solutions to the game.

Try creating a bigger game grid, such as M-10 M-x 5x5, and then run one of the crack commands below. The crackers will attempt to iterate their way to the best solution. This runs in real time and is fun to watch:

M-x 5x5-crack-mutating-bestAttempt to crack 5x5 by mutating the best solution.

M-x 5x5-crack-mutating-currentAttempt to crack 5x5 by mutating the current solution.

M-x 5x5-crack-randomlyAttempt to crack 5x5 using random solutions.

M-x 5x5-crack-xor-mutateAttempt to crack 5x5 by xoring the current and best solution.

Text Animation

You can display a fancy birthday present animation by running M-x animate-birthday-present and giving it your name. It looks rather cool!

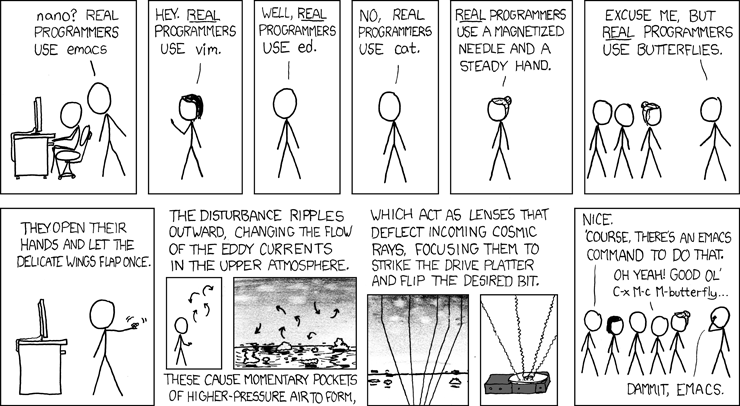

The animate package is also used by the M-x butterfly command, a command added to Emacs as an homage to the XKCD strip above. Of course the Emacs command in the strip is teeechnically not valid but the humor more than makes up for it.

Blackbox

The objective of this game I am going to quote literally:

The object of the game is to find four hidden balls by shooting rays into the black box. There are four possibilities: 1) the ray will pass thru the box undisturbed, 2) it will hit a ball and be absorbed, 3) it will be deflected and exit the box, or 4) be deflected immediately, not even being allowed entry into the box.

So, it’s a bit like the Battleship game most of us played as kids but… for people with advanced degrees in physics?

It’s another game that was added back in the 1980s. I suggest you read the extensive documentation on how to play by typing C-h f blackbox.

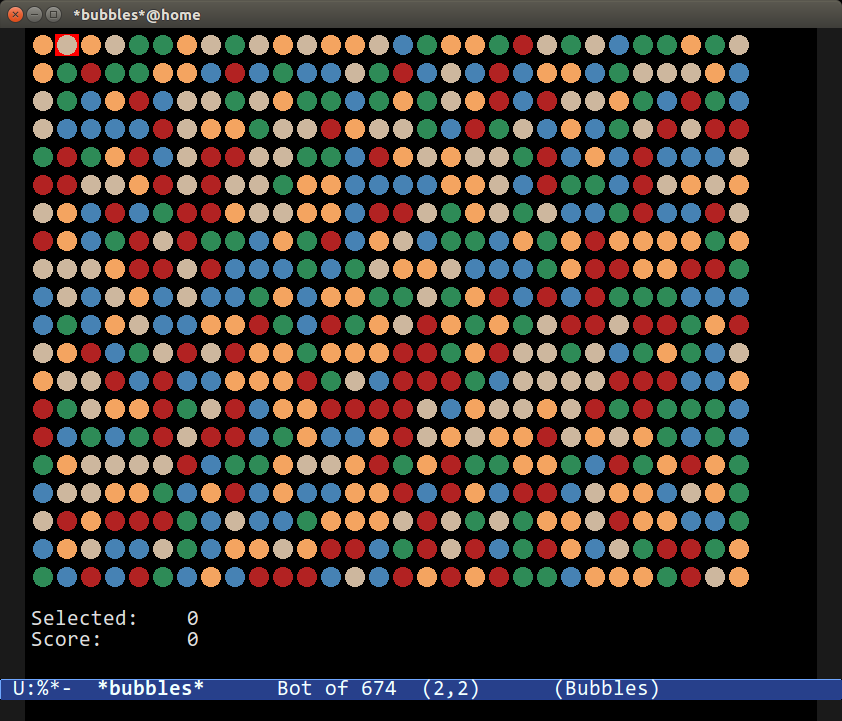

Bubbles

The M-x bubbles game is rather simple: you must clear out as many “bubbles” as you can in as few moves as possible. When you remove bubbles the other bubbles drop and stick together. It’s a fun game that, as an added bonus, comes with graphics if you use Emacs’s GUI. It also works with your mouse.

You can configure the difficulty of the game by calling M-x bubbles-set-game-<difficulty> where <difficulty> is one of: easy, medium, difficult, hard, or userdefined. Furthermore, you can alter the graphics, grid size and colors using Customize: M-x customize-group bubbles.

For its simplicity and fun factor, this ranks as one of my favorite games in Emacs.

Fortune & Cookie

I like the fortune command. Snarky, unhelpful and often sarcastic “advice” mixed in with literature and riddles brightens up my day whenever I launch a new shell.

Rather confusingly there are two packages in Emacs that does more-or-less the same thing: fortune and cookie1. The former is geared towards putting fortune cookie messages in email signatures and the latter is just a simple reader for the fortune format.

Anyway, to use Emacs’s cookie1 package you must first tell it where to find the file by customizing the variable cookie-file with customize-option RET cookie RET.

If you’re on Ubuntu you will have to install the fortune package first. The files are found in the /usr/share/games/fortunes/ directory.

You can then call M-x cookie or, should you want to do this, find all matching cookies with M-x cookie-apropos. Yes, that’s right: Emacs has a self-documenting apropos command to help you find the right fortune cookie message!

Decipher: Breaking Cryptograms

This package perfectly captures the utilitarian nature of Emacs: it’s a package to help you break simple substitution ciphers (like cryptogram puzzles) using a helpful user interface. You just know that – more than twenty years ago – someone really had a dire need to break a lot of basic ciphers. It’s little things like this module that makes me overjoyed to use Emacs: a module of scant importance to all but a few people and, yet, should you need it – there it is.

So how do you use it then? Well, let’s consider the “rot13” cipher: rotating characters by 13 places in a 26-character alphabet. It’s an easy thing to try out in Emacs with M-x ielm, Emacs’s REPL for Evaluating Elisp:

*** Welcome to IELM *** Type (describe-mode) for help.

ELISP> (rot13 "Hello, World")

"Uryyb, Jbeyq"

ELISP> (rot13 "Uryyb, Jbeyq")

"Hello, World"

ELISP>Simply put, you rotate your plaintext 13 places and you get your ciphertext; you rotate it another 13 and you end up where you started. This is the sort of thing this package can help you solve.

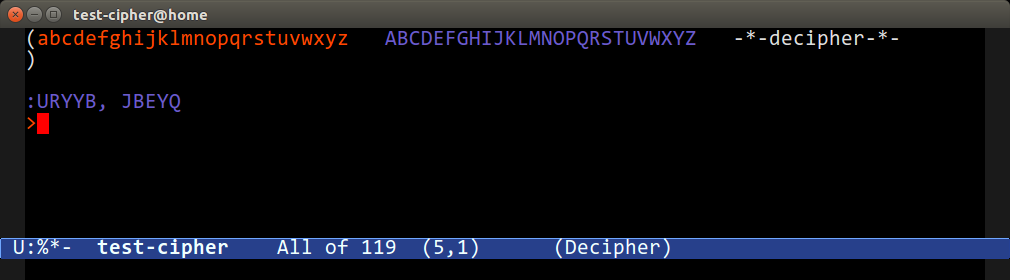

So how can the decipher module help us here? Well, create a new buffer test-cipher and type in your cipher text (in my case Uryyb, Jbeyq) and then start deciphering with M-x decipher.

You’re now presented with a rather complex interface. You can now place the point on any of the characters in the ciphertext on the purple line and guess what the character might be: Emacs will update the rest of the plaintext guess with your choices and tell you how the characters in the alphabet have been allocated thus far.

You can then start winnowing down the options using various helper commands to help infer which cipher characters might correspond to the correct plaintext character:

DShows a list of digrams (two-character combinations from the cipher) and their frequency

FShows the frequency of each ciphertext letter

NShows adjacency of characters. I am not entirely sure how this works.

MandRSave and restore a checkpoint, allowing you to branch your work and explore different ways of cracking the cipher.

All in all, for such an esoteric task, this package is rather impressive! If you regularly solve cryptograms maybe this package can help?

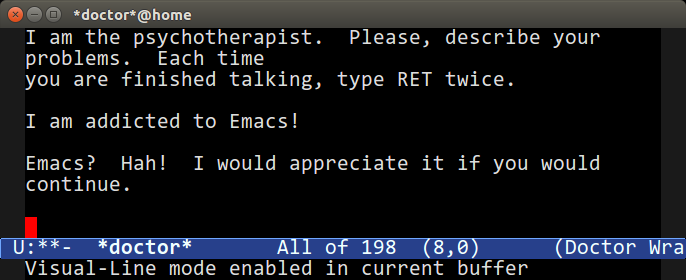

Doctor

Ah, the Emacs doctor. Based on the original ELIZA the “Doctor” tries to psychoanalyze what you say. Rather fun, for a few minutes, and one of the more famous Emacs oddities. You can run it with M-x doctor.

Yow! Zippy the Pinhead

Back in the day, you could call M-x yow and get a Zippy the Pinhead quote. Sadly Emacs no longer proffers the wisdom of Zippy due to legal restrictions. The module’s still there, so if you can source a yow.lines file from an older Emacs (pre Emacs 22) you can still enjoy his zany sayings.

There is, naturally, a M-x apropos-zippy command also for when you absolutely need to find the right Zippy quote.

More amusingly, there’s M-x psychoanalyze-pinhead so you can pit the good M-x doctor against Zippy in a battle of wits.

Dunnet

Emacs’s very own Zork-like text adventure game. To play it, type M-x dunnet. It’s rather good, if short, but it’s another rather famous Emacs game that too few have actually played through to the end.

If you find yourself with time to kill between your TPS reports then it’s a great game with a built-in “boss screen” as it’s text-only.

Oh, and, don’t try to eat the CPU card :)

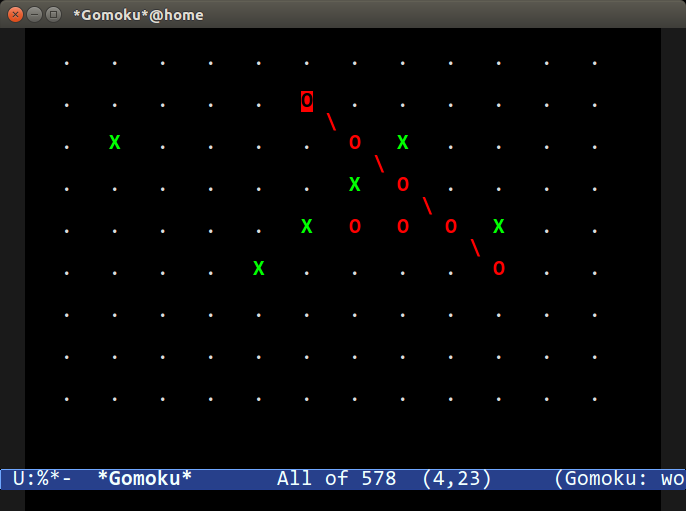

Gomoku

Another game written in the 1980s. You have to connect 5 squares, tic-tac-toe style. You can play against Emacs with M-x gomoku. The game also supports the mouse, which is rather handy. You can customize the group gomoku to adjust the size of the grid.

Game of Life

Conway’s Game of Life is a famous example of cellular automata. The Emacs version comes with a handful of starting patterns that you can (programmatically with elisp) alter by adjusting the life-patterns variable.

You can trigger a game of life with M-x life. The fact that the whole thing, display code, comments and all, come in at less than 300 characters is also rather impressive.

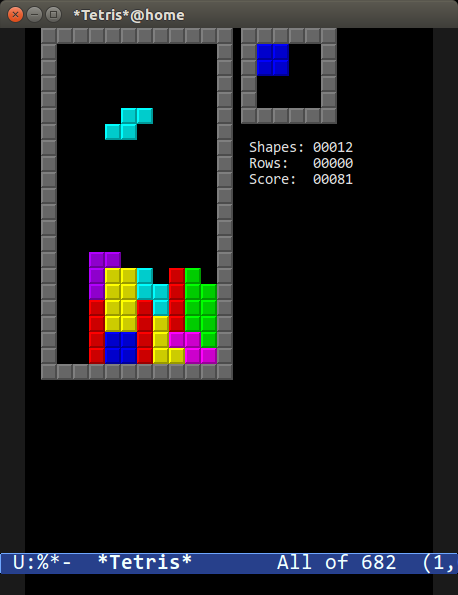

Pong, Snake and Tetris

These classic games are all implemented using the Emacs package gamegrid, a generic framework for building grid-based games like Tetris and Snake. The great thing about the gamegrid package is its compatibility with both graphical and terminal Emacs: if you run Emacs in a GUI you get fancy graphics; if you don’t, you get simple ASCII art.

You can run the games by typing M-x pong, M-x snake, or M-x tetris.

The Tetris game in particular is rather faithfully implemented, having both gradual speed increase and the ability to slide blocks into place. And because you have the source code you can finally remove that annoying Z-shaped piece no one likes!

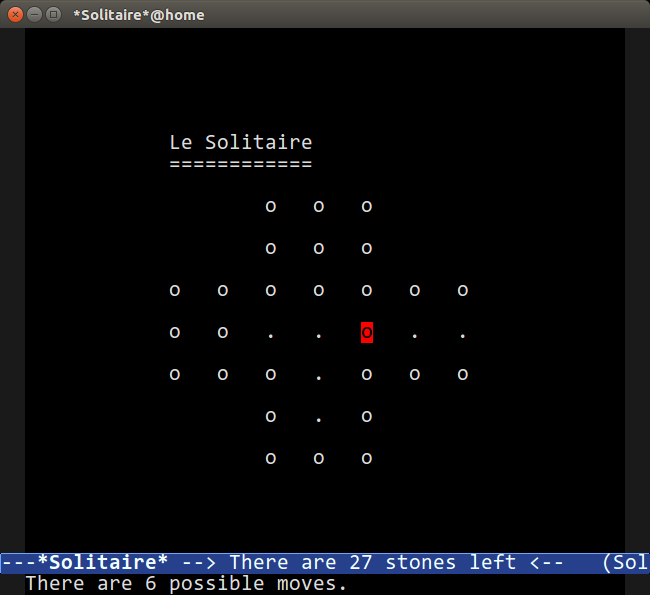

Solitaire

This is not the card game, unfortunately. But a peg-based game where you have to end up with just one stone on the board, by taking a stone (the o) and “jumping” over an adjacent stone into the hole (the .), removing the stone you jumped over in the process. Rinse and repeat until the board is empty.

There is a handy solver built in called M-x solitaire-solve if you get stuck.

Zone

Another of my favorites. This time’s it’s a screensaver – or rather, a series of screensavers.

Type M-x zone and watch what happens to your screen!

You can configure a screensaver idle time by running M-x zone-when-idle (or calling it from elisp) with an idle time in seconds. You can turn it off with M-x zone-leave-me-alone.

This one’s guaranteed to make your coworkers freak out if it kicks off while they are looking.

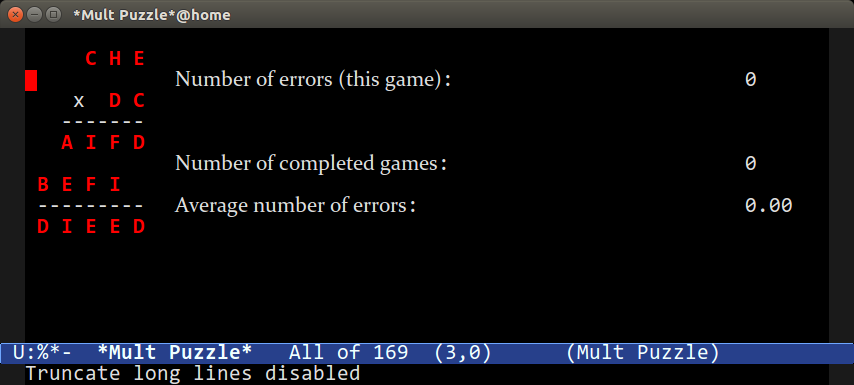

Multiplication Puzzle

This is another brain-twisting puzzle game. When you run M-x mpuz you are given a multiplication puzzle where you have to replace the letters with numbers and ensure the numbers add (multiply?) up.

You can run M-x mpuz-show-solution to solve the puzzle if you get stuck.

Miscellaneous

There are more, but they’re not the most useful or interesting:

- You can translate a region into morse code with

M-x morse-regionandM-x unmorse-region. - The Dissociated Press is a very simple command that applies something like a random walk markov-chain generator to a body of text in a buffer and generates nonsensical text from the source body. Try it with

M-x dissociated-press. - The Gamegrid package is a generic framework for building grid-based games. So far only Tetris, Pong and Snake use it. It’s called

gamegrid. - The

gametreepackage is a complex way of notating and tracking chess games played via email. - The

M-x spookcommand inserts random words (usually into emails) designed to confuse/overload the “NSA trunk trawler” – and keep in mind this module dates from the 1980s and 1990s – with various words the spooks are supposedly listening for. Of course, even fifteen years ago that would’ve seemed awfully paranoid and quaint but not so much any more…

Conclusion

I love the games and playthings that ship with Emacs. A lot of them date from, well, let’s just call a different era: an era where whimsy was allowed or perhaps even encouraged. Some are known classics (like Tetris and Tower of Hanoi) and some of the others are fun variations on classics (like blackbox) — and yet I love that they ship with Emacs after all these years. I wonder if any of these would make it into Emacs’s codebase today; well, they probably wouldn’t — they’d be relegated to the package manager where, in a clean and sterile world, they no doubt belong.

There’s a mandate in Emacs to move things not essential to the Emacs experience to ELPA, the package manager. I mean, as a developer myself, that does make sense, but… surely for every package removed and exiled to ELPA we chip away the essence of what defines Emacs?